Lost in Translation: Returning Home

In the summer of 1945, as World War II neared its end, the Allied powers issued the Potsdam Declaration, demanding Japan’s unconditional surrender. Reporters pressed Japanese Prime Minister Kantaro Suzuki for a response. He chose the word “mokusatsu.”

In Japanese, mokusatsu is a layered term. It can mean “we withhold comment for now,” a cautious way of buying time. But it can also mean “we treat this with silent contempt.”

When American interpreters translated Suzuki’s statement, they chose the harsher meaning: open defiance. To U.S. officials, it seemed Japan had dismissed the ultimatum outright. Days later, the United States dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, bringing the war to a devastating close.

Historians still debate whether a mistranslation changed the course of history. What is certain is that one ambiguous word—mokusatsu—became a powerful reminder of how much can hinge on language, and how easily nuance can be lost in translation.

History shows us that when words are misunderstood, the consequences can be enormous—sometimes even catastrophic. Yet while not every mistranslation changes the course of nations, the way we understand language deeply affects our perception of life. Words shape our identity, our values, and our behavior. They carry not just definitions, but resonance. The language we choose can either limit or expand how we relate to the world around us, and to our Divine mission.

While prayer in any language is accepted by G-d when offered sincerely, the original Hebrew of our prayers carries a holiness and energy that is difficult to capture in other tongues. This is why, whenever possible, it is meaningful to express—even a few select prayers—in their original words, and to probe the deeper meaning that lies within them.

One of the most powerful refrains of the High Holiday liturgy declares:

“But teshuvah, tefillah, and tzedakah remove the severity of the decree.”

Commonly translated as repentance, prayer, and charity, these words convey far more than their English equivalents suggest. They are uniquely Jewish concepts that cannot be captured by simple translation. In fact, their common renderings can even obscure their true meaning.

Teshuvah – Returning

The usual translation, repentance, evokes regret, remorse, and the resolve to start a new chapter. Teshuvah, however, actually means to return (from the root tashuv = return). It is not about becoming someone new, but about coming back to who we truly are. At our core, the Jewish soul is good and pure. Sin is not our essence but an external layer that can be shed. Teshuvah means to return home—to rediscover and realign with our truest self. This is why it applies to everyone, no matter their current state.

Tefillah – Connection

The English word prayer suggests pleading for needs, a one-way request. But tefillah is about connection (from the root tofel = to join or connect). Even when we lack nothing, tefillah is essential because it binds us to G-d in a relationship. Yes, we present our requests, but at its heart, tefillah is not about asking—it is about being present with the One to whom we belong.

Tzedakah – Justice

Charity implies benevolence, an act of generosity when one gives beyond obligation. But tzedakah comes from tzedek—justice, righteousness. What we give is not “ours” to keep; it is entrusted to us by G-d to be shared with others. Supporting those in need is not an act of extra kindness, but the fulfillment of a responsibility.

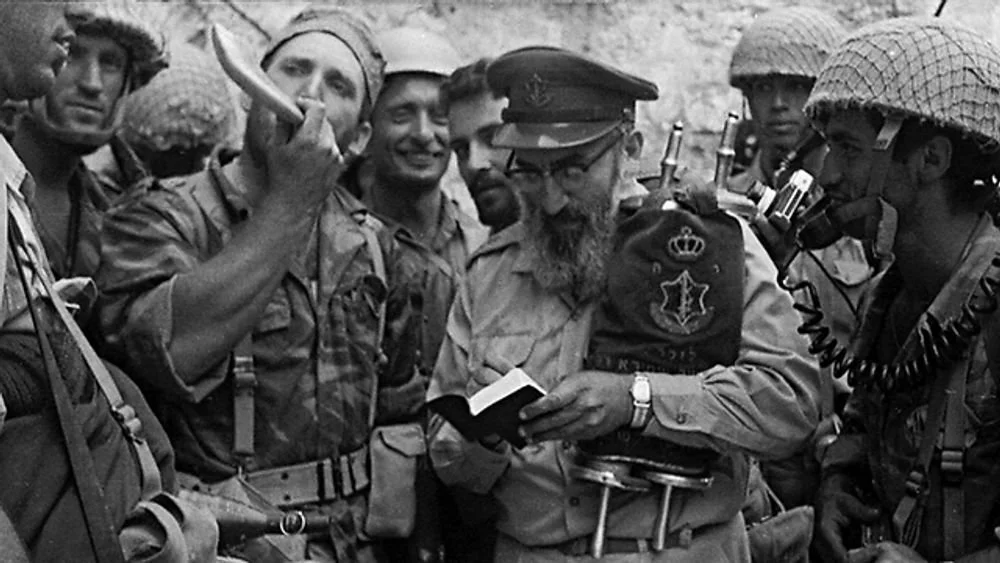

The Shofar – The Cry of the Child Returning

The Baal Shem Tov told a parable: A king sent his beloved son to a far-off land to learn about the people of his vast kingdom so he could one day inherit the throne. Squandering his wealth, the son became destitute. Longing to return home, he reached the palace gates but had forgotten his native tongue. Unable to explain himself, he cried out. The king recognized his voice and embraced him with love.

So it is with us. The King is G-d, and we are His children. Our soul, sent into this world to transform it and elevate it, sometimes forgets its origin. On Rosh Hashanah, the shofar becomes our wordless cry—a sound beyond language, beyond translation—that pierces heaven. It is the cry of the child longing to return home. And G-d, our Father, recognizes that cry, embracing us and blessing us with a good and sweet new year.

Coming Home Together

Parshas Nitzavim describes the future redemption when: “Then the Lord, your God, will bring back your exiles... He will once again gather you from all the nations.” (Deuteronomy 30:3) Rashi explains that it is as though G-d Himself gathers each person one by one, for each soul has an irreplaceable role in the divine plan. Teshuvah is not just our return to G-d—it is G-d’s embrace of us, His children, who are indispensable to creation’s purpose.

When the time of Redemption arrives, the Torah teaches that Jews from around the world will return home to Israel and live in peace with all nations on earth.

Teshuvah calls us back to our essence. Parshas Nitzavim teaches that no Jew is left behind—every individual matters. And the shofar gives voice to our deepest longing: to come home.

As we enter the new year, let us pray for the safe return of the hostages, for the safety of our brothers and sisters in Israel and around the world. May we each find our way home—spiritually, communally, and personally. May G-d grant you and your family health, happiness, and blessing. And may the great shofar soon sound, gathering us all from the four corners of the earth, bringing the ultimate redemption and peace to the world!